Written and delivered by Rebecca Slough on Friday, February 7, 2025

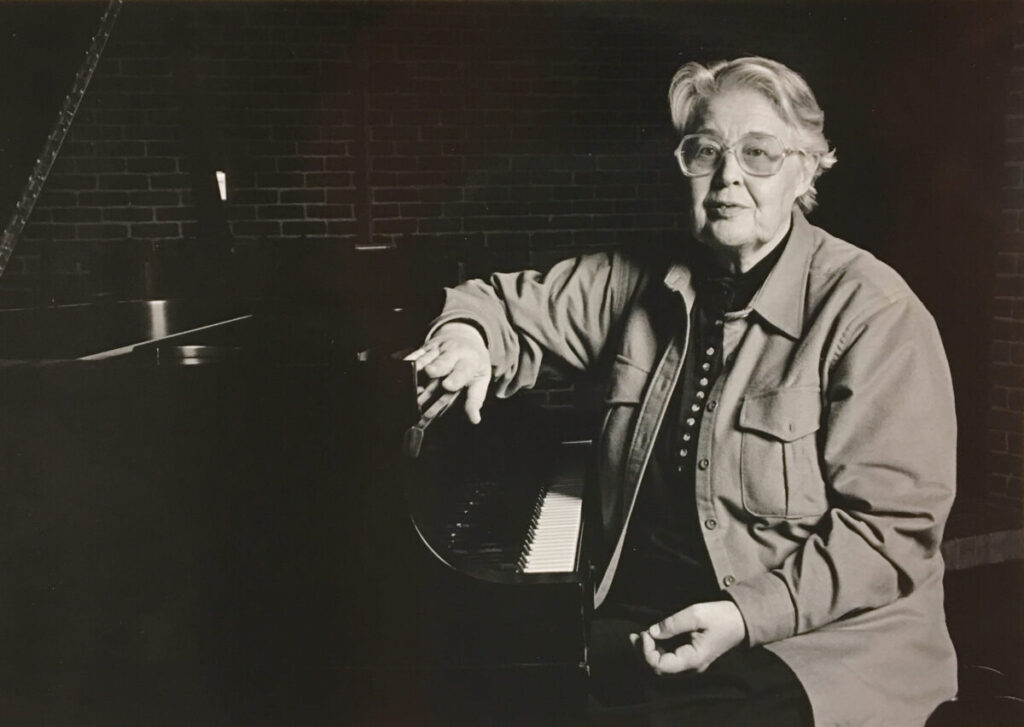

Mary Kathryn Oyer was an amazing human being, whose life and teaching touched thousands of people over her 100 years of living.

She was a presenter at three Mennonite Arts Weekends:

- In 1994 and 1996 – the second and third weekends and

- In 2002 when she was nearly 80 years old.

Mary’s training as a musician started in second grade when she learned to read music and started playing piano. By age 7 people recognized that she had perfect pitch (later in life she said this gift was almost useless in learning African music). In the fifth grade she announced to her sister, Verna, that she would become a music teacher; the next year she started playing cello.

Mary recognized that “learning music was a privilege [she said]…it connected me with people who were giving something that they valued.”1

Mary was surprisingly prescient in her vocational announcement to her sister because she is best known and loved as a generous, engaging, and knowledgeable teacher.

She began teaching at Goshen College at the age of 22. She was given the responsibility to develop a new introductory fine arts course that was to build knowledge skills for both music and the visual arts. Few schools had taken this approach to music and art appreciation, and it was not an easy experience for a young woman in 1945, whose primary instrument was cello, not voice or piano.

A few church leaders and some GC students wondered publicly how “Mary Oyer could be a Christian and play the cello.” Throughout her 20s and 30s Mary wrestled with questions of faith, vocation, aesthetics, and teaching. These questions guided the coursework and the papers she wrote for her doctoral studies. Sad to say, Mary found the best guides and greatest helpers in thinking through these questions were people from other denominational traditions and not Mennonites. But thank God they were there for her. Mary found a way to stay within the Mennonite Church and still integrate the outcomes of her struggles with these deep life questions.

Mary did not learn to appreciate hymns as serious art forms until her late 30s and early 40s when she was invited to serve as the secretary and only woman on a hymnal committee called together to compile a collection for the Mennonite Church and the General Conference Mennonite Church. She brought her skills of musical and historical analysis to these short tunes and poetic forms. The richness she found in them was a continual surprise to her. That collection, the“red hymnal”, was published in 1969.

In my opinion, this hymnal work began shifting Mary’s focus as a musicologist who studied specific musical works to becoming an ethnomusicologist. She started asking different kinds of questions about music and its role in human communities. For example:

- What does a hymn show about a people’s culture? Their artistic sensibilities? Their social practices?

- How do hymns function within particular groups of people?

- Why has a hymn endured over generations or goes out of use in one generation?

Mary’s work on the hymnal with questions like these helped her make peace with gospel songs. She came to understand why they are meaningful for many people in particular places with particular experiences. She threw off the “gospel song taboo” that was promoted by the Goshen College music faculty. She felt the freedom to lead these songs in many congregations as she traveled across the church without having to make a judgment about the genre as a whole.

I’ve traced some of Mary’s early history to help us see how she was set on a life trajectory that kept expanding her worldview and personal experience.

- From a young age, she recognized that music brings us into relationships with each other, especially when we sing together.

- The questions that we ask about specific types of music, the people who bring it to life, and their places in the world can change our perspectives. We can hear and understand musical styles differently and with less judgment.

Mary’s perspective on the world – its many people, their ways of worship, and most importantly her self understanding – changed radically as she studied music with local musicians in Africa and later taught in Taiwan as a foreigner. People who knew Mary as a younger person were dismayed by these changes in her ways of hearing and seeing things. Her opinions were no longer clear and final.

There are qualities that Mary developed over the course of her life that, I think, became clearly reflected in the ways that she taught and in her endless interest in other people.

Mary developed a generous spirit – she was warm, glad to see people that she knew and glad to meet those people that she did not know. She offered them whatever she could by way of personal attention, affirmation, and appreciation. She remembered many of the people she met to the end of her life.

- Mary had a profound trust in ideas, feelings, viewpoints,and artworks that she found worthwhile. She was a good judge of what was trustworthy.

- As she aged, Mary became more open-minded. She continued the practice, which she started at age 22, of immersing herself deeply in artworks from many cultures. She valued their histories, the places where they were created, and the people who created them. She pursued the question: what is the work doing? As the work revealed its answers, her understanding and perspectives grew wider, but did not automatically replace other perspectives that she held.

- Mary was adventuresome, and she learned to trust people. Whether going to Scotland alone as a single woman in the 1960s, or her years of trekking around the African continent, or traveling across the US and Canada to lead singing in many congregations, she embraced new opportunities with courage and anticipation.

- Words like fresh, imaginative, lively, astonishing, stimulating, remarkable, lovely – peppered her conversations in the 40 years that I knew Mary. Her use of these words revealed something important about what she hoped for and expected to experience in life. They move very close to experiences of surprise, revelation, epiphany, and perhaps, even an encounter with the presence of God.

Mary gave herself to relationships with all kinds of people and shared her knowledge of things that she valued most.

Thanks be to God.